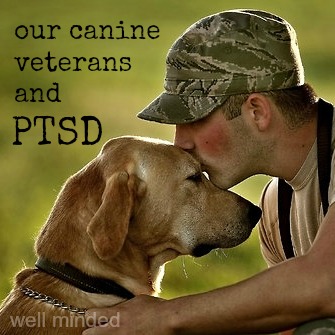

We often hear about how so many of our veterans suffer from PTSD, or Post-traumatic Stress Disorder, a heartbreaking condition that is defined by the Mayo Clinic as "a mental health condition that's triggered by a terrifying event–either experiencing it or witnessing it. Symptoms may include flashbacks, nightmares, and severe anxiety, as well as uncontrollable thoughts about the event." Sometimes individuals with PTSD are partnered with a service dog who can help them manage their symptoms. But can dogs who have seen combat also get PTSD?

The answer is yes.

Over the past few years, more research is being done surrounding canine PTSD. Military dog specialists are recognizing it and learning how to treat it.

Cora, a Belgian Malinois, went off to Iraq as a bomb-sniffing dog. She loved her work and treated her training and her job as a game or play session. Air Force Tech. Sgt. Garry Laub, who trained Cora before she deployed said, "She knew her job. She was a very squared-away dog."

Cora went on dozens of combat patrols in Iraq over the course of several months, and her easy-going, focused spirit began to change. Loud noises startled her, and she became more aggressive. It is thought that her PTSD was not the result of a single traumatic event, but of an accumulation of stress as a result of the intense, emotional situation in which she worked.

Click here to read Tony Perry's Los Angeles Times Article featuring Cora's story.

Military canines experience the same war environment that their human counterparts do, and they can just as easily be affected. It is estimated that half of the dogs who return from war with PTSD can be retrained for employment within the government, such as with police departments, border patrol, or the Department of Homeland Security. If the animal is unable to work, he is retired and made eligible for adoption as a family pet.

Army 1st Sgt. Casey Stevens spoke about his dog, Alf, and summarized the sentiment regarding military canines: "He saved my life several times; he had my back. Some guys talk to their dogs more than they do to their fellow soldiers. They're definitely not equipment."

James Dao, for the New York Times, wrote:

If anyone needed evidence of the frontline role played by dogs in war these days, here is the latest: the four-legged, wet-nosed troops used to sniff out mines, track down enemy fighters and clear buildings are struggling with the mental strains of combat nearly as much as their human counterparts. By some estimates, more than 5 percent of the approximately 650 military dogs deployed by American combat forces are developing canine PTSD.

Canine PTSD has been gaining more attention in the past few years, and is really a new diagnosis since we have exposed our military dogs to the combat-related violence in Iraq in Afghanistan. It manifests itself in different ways, as does human PTSD. Dao elaborates:

Like humans with the analogous disorder, different dogs show different symptoms. Some become hyper-vigilant. Others avoid building or work areas that they had previously been comfortable in. Some undergo sharp changes in temperament, becoming unusually aggressive with their handlers, or clingy and timid. Most crucially, many stop doing the tasks they were trained to perform.

Thankfully, as veterinarians and canine military experts work with dogs who suffer from PTSD, more treatment and resources become available. The condition is most treated with behavior modification techniques and/or anti-anxiety drugs.

So this Veteran's Day, as we honor our soldiers, many of whom suffer from PTSD, let's also think about their canine counterparts, thank them, and wish them well on their journey to recovery.

You might also enjoy:

Veteran's Day in the Eyes of the Children of a Pet Sitter

Photo source: Bryce Harper for the New York Times, nytimes.com.